All At The Same Time

The question facing Congress is how to beat China back to the Moon while not abandoning Low Earth Orbit to China either. In Jared Isaacman’s confirmation hearing, he asserted that we could not only accomplish both goals but also go to Mars at the same time. The Commerce Committee members present at the hearing were skeptical, as was much of the space sector. We assert that this is because the current paradigm of space exploration is stuck in a mental rut.

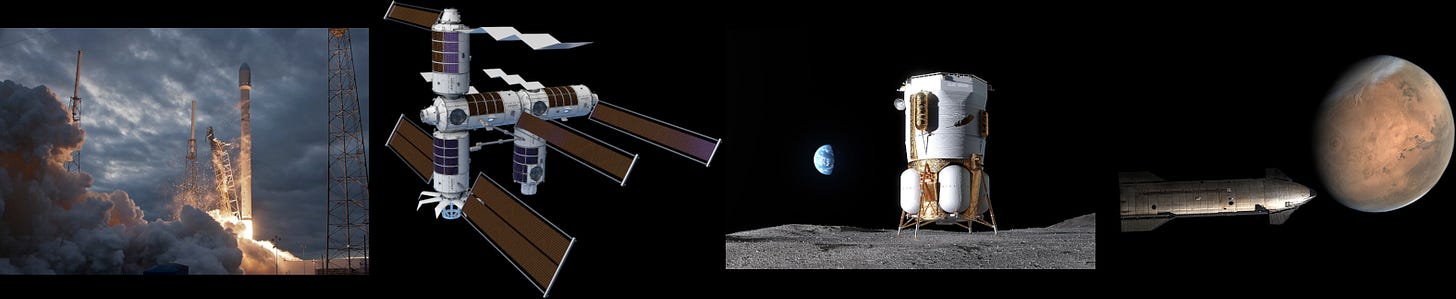

The United States must lead not only in space exploration but also in building the economic, industrial, legal, and governing foundation for humanity's permanent presence beyond Earth. That leadership cannot and should not rest solely on the shoulders of NASA or any government program of record. Instead, it must be driven by a dynamic, competitive, and well-capitalized private sector that is empowered to pursue the four essential pillars of national space ambition: 1) First in Launch, 2) First in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) Development, 3) First in Lunar Development, and 4) First to Mars.

To achieve these objectives, the United States must use every tool of national power—tax policy, financial incentives, legal and regulatory frameworks, procurement systems, diplomacy, and cultural signaling—to enable private enterprise to lead. This paper outlines a comprehensive strategy to align these instruments with each of the four space development pillars.

Superiority in Launch, LEO, Moon, and Mars

The elements of that unspoken debate was the ability to maintain the US supremacy in four primary areas that enable supremacy in others:

1. First in Launch - Ensure U.S. commercial launch providers continue to provide transformational services to the global market share, cadence, and innovation.

2. First in LEO Market Development - Establish U.S.-led commercial leadership in LEO through stations, manufacturing, tourism, and services.

3. First in Lunar Development - Build a U.S.-aligned, private-sector-driven industrial ecosystem starting at the lunar South Pole and continuing across the Lunar surface.

4. First to Mars - Enable American and allied firms to lead humanity’s first permanent settlement of Mars.

National Policy Tools for Industrial Mobilization

The question Isaacman’s confirmation panel raised when he suggested that NASA could service Low Earth Orbit, economically develop the Moon, and build bases on Mars “at the same time” was how you could fit all of that in NASA’s budget. Their incredulity demonstrated a blind spot that has plagued space policy since Apollo: that everything we do in space is a NASA-funded program of record. What we argue here is that not only is this wrong, but when you look at how the rest of our government works with public/private partnerships, it isn’t how we do anything else. Each of the following sections demonstrates the various tools used by the US Government to support emerging markets.

Tax & Capital Formation

Encouraging capital formation is essential for industries that require high upfront investment and long return cycles—like space launch, orbital infrastructure, and extraterrestrial development. The following tools address private capital's risk/reward mismatch and create predictable, long-term incentives for investors to deploy resources into space-focused enterprises.

100% expensing for space infrastructure: Allowing firms to fully deduct capital expenditures on launchpads, spacecraft factories, or in-orbit platforms in the year incurred (rather than amortizing over time) incentivizes immediate investment. This tool was successfully deployed in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (26 U.S.C. §168(k)) to stimulate domestic manufacturing. A space-specific extension could expand eligibility to include extraterrestrial construction, such as lunar surface assets or Mars transit vehicles.

200% expensing for strategic frontier infrastructure: For a defined category of high-risk, frontier-expansion projects (e.g., lunar power grids, in-space propellant depots, Mars ISRU nodes), Congress could authorize a super-deduction of 200% of qualifying capital investment. This has precedent: the UK implemented a 130% "super-deduction" in 2021 to accelerate post-COVID manufacturing investment. A 200% expensing rule would make strategic infrastructure cheaper to build than not to build, especially for firms operating under tight cashflow models.

Capital gains tax holidays for space-sector reinvestment: Temporarily exempting capital gains taxes on profits reinvested into space ventures reduces investor hesitation and encourages portfolio rotation into high-risk sectors. Modeled on Opportunity Zones (26 U.S.C. §1406Z), this could be expanded to cover investments in qualified "Space Development Corridors" including LEO-based industrial nodes, cis-lunar transport corridors, or Mars-focused infrastructure.

Tax-exempt space bonds: Authorizing municipal-style tax-exempt bonds for space infrastructure projects (such as orbital power, spaceports, or lunar communications) allows access to lower-cost capital from long-term institutional investors. A federal designation of "Space Infrastructure Bonds" would create a new category of investment, similar to how airports and utilities finance public goods. These bonds could be underwritten by a new federally chartered Space Development Bank.

Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) enhancements for space startups: While 26 U.S.C. §1202 already applies to many space companies, the current $50 million asset cap limits its utility for firms scaling complex hardware. Raising the asset threshold to $1 billion for designated "space industrial enterprises" and increasing the exempted capital gains ceiling to $500 million per investor would significantly increase venture-scale capital inflow. This reformed "QSBS-Space" tier would resemble the early biotech carve-outs that enabled robust IPO pipelines and institutional entry.

These tools collectively de-risk early capital deployment, enable higher ROI for successful ventures, and align federal tax policy with long-term national strategy. Importantly, they allow the government to incentivize outcomes without directing programs—letting private enterprise pursue strategic goals with market speed.

Finance & Risk Mitigation

Space infrastructure is capital-intensive and high-risk, with long time horizons and high technical uncertainty. Private capital is often unwilling to bear this risk without support, especially for first-of-kind systems or undeveloped markets. The federal government can act as a catalytic insurer, financier, and purchaser of last resort through the following mechanisms:

Government loan guarantees for infrastructure and transport: Similar to those used by the Department of Energy for nuclear and clean energy projects, federal loan guarantees reduce risk to lenders by backing a portion of the loan’s principal. This enables large-scale investments in high-risk but high-reward projects like reusable launch systems, propellant depots, and lunar communications. The Ex-Im Bank or a new "Space Credit Authority" could fulfill this role.

Loss absorption funds for first movers: Modeled after programs like the U.S. Crop Insurance Program or airline war risk insurance, a federal risk pool could underwrite a portion of direct losses for early commercial missions that fail due to technical or environmental uncertainties. This could accelerate early lunar and Mars logistics without requiring direct subsidies.

Federally backed milestone payments and offtake agreements: Rather than cost-plus contracting, government entities could issue milestone-based funding tied to development, demonstration, and delivery targets. Additionally, fixed offtake agreements (e.g., purchase of oxygen, water, power) provide reliable demand that enables private financing. This model is widely used in energy procurement and was instrumental in the growth of solar and wind via power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Public-private lunar infrastructure investment vehicles: A new structure akin to a Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) or a Space Infrastructure Development Corporation could allow private capital to pool resources into lunar assets (e.g., landing pads, habitats, power stations) with limited liability and government matching. This would blend the familiarity of conventional investment vehicles with the novelty of space development.

These mechanisms reduce downside risk, improve capital access, and convert one-off government funding into long-term economic multipliers. Importantly, they allow risk-bearing to shift to the private sector only once infrastructure and markets begin to mature—exactly as was done with early railroads, aviation, and telecom.

Legal and Regulatory Certainty

For capital to flow and long-term operations to be viable, private actors must have clarity and confidence in legal rights and regulatory stability. A patchwork of temporary waivers or ambiguous international interpretations deters large-scale investment. Government must act to provide reliable legal scaffolding.

Codification of space resource rights (51 U.S.C. §51303): While current U.S. law affirms that U.S. citizens may own extracted space resources, the statute is narrow and underutilized. Congress should expand this language to include clear property use and exclusion rights for lunar and Martian operations, modeled on terrestrial mineral leasing law. Bilateral treaties under the Artemis Accords can reinforce these claims without triggering sovereignty concerns under the Outer Space Treaty.

Indemnification and liability caps for launch and in-space operations: Current indemnification under 51 U.S.C. §50907 limits government coverage to third-party claims resulting from launch mishaps. This regime should be extended to cover lunar landing and in-space servicing activities, with higher caps and predictable payout rules. The nuclear industry’s Price-Anderson Act provides a proven analog, offering capped liability and a shared compensation pool in exchange for industry compliance.

Streamlined, mission-style licensing under Office of Space Commerce: The current commercial space licensing framework (14 CFR Part 450) is a positive step, but should be made more dynamic. For multi-launch providers and long-duration infrastructure operators, a mission-class license—valid for a category of vehicles, destinations, or orbits—could dramatically reduce time and cost of compliance. This is comparable to blanket licenses used by the FCC for satellite constellations.

Preemption of state/local NEPA-style blockers for launch infrastructure: Major U.S. launch sites and spaceports can be delayed or obstructed by local environmental or zoning reviews. Congress should preempt such interference for any infrastructure deemed part of a "National Space Industrial Base" under 10 U.S.C. §2501, akin to how interstate pipelines and railroads receive federal siting authority. NEPA compliance should be streamlined under a categorical exclusion or programmatic EIS for commercial space corridors.

Recognition of operational zones and non-interference principles: Building on the Artemis Accords, the U.S. should codify into domestic law a right to non-interference within operational zones established by U.S. entities conducting resource extraction or infrastructure development. This would provide the legal foundation for safety zones, staging areas, and logistical hubs on the Moon and Mars, allowing industry to invest confidently in long-term surface operations.

By addressing legal ambiguity proactively, the United States can ensure its companies operate under a stable, predictable legal regime that signals strength, fairness, and strategic intent. This mirrors the legal certainty provided to the oil and gas industry in the mid-20th century, which enabled massive private-sector-led frontier expansion.

Trade & Diplomatic Leverage

Space is not only an industrial frontier but a geopolitical one. China, Russia, and Europe are deploying state-backed space enterprises to project power and claim emerging markets. U.S. strategy must blend multilateral diplomacy, bilateral partnerships, and trade enforcement to ensure open markets and American-aligned norms.

Space-focused trade policy: targeted reciprocity, not hypocrisy: While U.S. support for domestic space firms includes tax policy, loan guarantees, and procurement contracts, it avoids direct state ownership, exclusive market allocation, or zero-risk bailouts. Trade policy should challenge true market distortions abroad—e.g., subsidies tied to national carriers (Ariane), closed procurement systems (China), or below-cost launch pricing. The U.S. should lead efforts in WTO, OECD, and bilateral frameworks to define and ban predatory space subsidies while defending outcome-oriented public-private models.

International MOUs for lunar resource zones: Building on the Artemis Accords, the U.S. should pursue detailed Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with key allies (e.g., Japan, UAE, Luxembourg, Australia) to coordinate non-interference zones, power grids, navigation standards, and infrastructure interconnectivity. These agreements allow private firms to operate within a trusted ecosystem without the friction of multilateral consensus.

Integrate space into Five Eyes, NATO, and AUKUS industrial planning: Just as defense supply chains and intelligence architectures are harmonized across trusted partners, space capabilities (including launch, data relay, and lunar comms) should be treated as shared national assets. This reduces redundancy, opens markets for U.S. firms, and helps counter China’s growing use of space as a diplomatic wedge.

Declare commercial space a national security imperative: The White House, DoD, and State Department should formally recognize the commercial space sector as a strategic industry, akin to semiconductors or energy. This designation would unlock special trade protections, industrial base programs (under 10 U.S.C. §2501), and export flexibility under ITAR/EAR. It also strengthens the narrative for U.S. firms operating abroad.

Lead in setting commercial norms for Mars and beyond: As settlement-scale operations become viable, the U.S. should preemptively define the norms of interplanetary commerce, jurisdiction, and reciprocity. This includes promoting open standards, transparency, private ownership of extracted resources, and dispute resolution mechanisms compatible with liberal democratic values.

This approach is not "good for me but not for thee" – it is a defense of competitive commercial ecosystems against opaque, state-controlled industrial policy. The goal is not to ban all state involvement, but to constrain models that deny market access or eliminate risk through political fiat. America's greatest advantage remains its innovation economy—if we preserve room for it to operate.

Procurement & Demand Signaling

One of the most effective—and underutilized—tools of government is being a customer. The U.S. government doesn’t need to own the infrastructure or run the missions; it can shape markets by simply buying services in a way that reduces risk, sets standards, and creates revenue certainty for emerging firms. This is not industrial policy in the central-planning sense. It is demand shaping, and it is how nearly every major U.S. industry—aviation, semiconductors, nuclear power, and pharmaceuticals—reached scale.

Multi-agency coordinated purchasing of launch, logistics, and communications: Agencies like NASA, DoD, NOAA, DHS, and even NIH can pool purchasing power under a National Space Acquisition Initiative. Instead of duplicating efforts, they can issue joint solicitations for launch services, orbital transport, data relay, and lunar delivery. This creates stable demand signals while avoiding stovepiped contracting.

Fixed-price lunar power, water, and resource delivery contracts: Rather than building infrastructure themselves, federal agencies should specify what they want delivered—e.g., 10kW of continuous power at Shackleton Crater, or 500kg of water on a specified date. Whoever delivers it gets paid. This approach turns Moon-based resources and logistics into an open marketplace. The model mirrors how utilities purchase electricity or how DoD contracts for fuel at forward operating bases.

Strategic Space Commodities Reserve: To complement fixed-price contracts, the U.S. could establish a Strategic Space Commodities Reserve (SSCR) to serve as a long-term price floor and logistical buffer. Modeled on the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and federal stockpiling programs for rare earths and medical supplies, the SSCR would act as a purchaser of last resort for key in-space commodities like water, oxygen, hydrogen, and regolith-derived feedstocks. The government would pay storage fees to firms maintaining inventories of these commodities at designated depots (e.g., LEO, L1, lunar orbit, or surface). This not only incentivizes surplus production, but stabilizes nascent markets with guaranteed offtake capacity.

Prizes for milestone achievement in settlement infrastructure: Large, DARPA/XPrize-style awards should be authorized for high-risk, high-value breakthroughs—first privately developed lunar regolith processor, first 100-day closed-loop habitat test, first Mars surface relay station. These prizes incentivize creativity, attract private capital, and avoid bureaucratic overreach. Crucially, they pay only for success.

Guaranteed service contracts for Mars autonomy and logistics: The government can act as the first customer for deep-space communication relays, autonomous mission controllers, and bulk logistics services for Mars missions. These contracts create minimum viable revenue for firms tackling otherwise speculative challenges. Think of it as the equivalent of Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS), but for deep space.

Long-term advance market commitments (AMCs): Modeled on those used in global health (e.g., vaccine development), AMCs can guarantee minimum purchases of in-space goods (oxygen, materials, pharmaceuticals) or services (assembly, repair, telemetry). This gives private firms the revenue predictability needed to raise capital and build capability.

Procurement reform for agility and speed: All of the above will fail if shackled to the traditional federal acquisition system. Congress should authorize flexible, OTA-like authorities across civil agencies—not just DoD—and mandate timeline-driven procurement windows for new space solicitations. Private-sector speed must be matched by procurement agility.

Procurement and demand signaling transform government from a funder of programs to a buyer of futures. This approach preserves private-sector leadership while pulling forward whole markets through committed purchasing. It is the original American model—from clipper ships to commercial aviation—and it must now be applied to space.

Strategic Signaling & Public Mobilization

Industrial revolutions are not just technological or financial events—they are cultural shifts. The United States must openly, visibly, and unambiguously declare that space is not just a scientific endeavor, but the next great economic frontier of the American project. The public must see it, students must study it, and entrepreneurs must believe it.

Joint Resolution of Congress: America’s Economic Frontier in Space: Congress should pass a bipartisan Joint Resolution declaring the development of space as a vital national interest and the next chapter in American prosperity. The resolution should establish specific long-term national goals, including:

Enabling 5,000 Americans living and working in space by 2040

Achieving 10% of U.S. GDP from space-related industries by 2040

Establishing a self-sustaining economic zone on the Moon by 2035

Landing the first commercially-led human mission to Mars before 2040 These goals should be reinforced annually in the President’s Economic Report and included in strategic reviews (e.g., NSS, NDS, and OSTP priorities).

National Space Leadership Act: Beyond a resolution, Congress should pass a law declaring that U.S. national space strategy will prioritize private-sector leadership, competitive markets, and frontier settlement. This act would serve as a guiding star for all subsequent regulation, procurement, and international diplomacy.

Presidential address: The New Frontier Doctrine: A President should address the nation and the world, articulating a “New Frontier Doctrine” that frames the expansion into space not just as science or security, but as the continuation of the American spirit of open frontiers, free enterprise, and democratic leadership.

Public-private “Space Industrial Corps”: Launch a new civilian-national service pipeline in partnership with industry, similar to the 20th-century Civilian Conservation Corps or ROTC. Students would rotate through space companies and frontier infrastructure projects, building a workforce with the skillset and mindset for off-world development.

Civic integration into education and local economies: Space should be integrated into K-12 and university curricula as a driver of jobs and prosperity, not just STEM inspiration. Federal education grants could prioritize programs that partner with industry, simulate in-space economic scenarios, or prepare students for orbital and lunar careers.

National Space Heritage Initiative: Celebrate and preserve milestones of U.S. commercial space achievements through national parks, museums, and public memorials—creating cultural continuity from Apollo to Artemis to Axiom and beyond.

This is not about manufacturing nostalgia. It’s about forging identity. Strategic signaling tells every American—and every competitor—that space is not a niche; it is a destiny. And we will shape it.

Go. Everywhere. Now.

The primary point of these examples is to stop thinking of our ambitions in space, AI, quantum computing, or new sources of energy as a “program”. Instead, it is an emerging economic frontier that is so transformative that leaving it to one Agency’s “program of record” or publishing yet another “national strategy” would be an incredibly grave strategic error. America’s leadership in space must be commercial, ambitious, and fast. This is a call for every American to understand that the future is so fantastically full of potential that it requires aligning every tool the United States has behind private sector success. The stars are not a distant dream but an immediate and existential industrial objective. And we must act like it.

Go.

Everywhere.

Now.

We talk to both.

The paths outlined offer ways to encourage the demand side for use of space, and avoid the trap of beseeching the government to fund massive programs.

The Foundation is working to bring more people to see how space can be used to accomplish their goals, not trying to convince people to change their goals.

This is a superb document. Using analogies of pre-existing governments incentives really helps drive home the ability to build the space infrastructure we need to expand humanity off-world.